Poetry isn’t always emphasized in early school years. While young students are encouraged to read story books, they might at best receive a lukewarm introduction to reading poems. Recalling his education, poet Jack Prelutsky said, “Sometime in elementary school I had a teacher who, in retrospect, did not like poetry herself… She would pick a boring poem from a boring book and read it in a boring voice, looking bored while she was doing it.”

Exposure to approachable, vital poems will help children grow out of their negative perceptions of poetry, maybe even discovering a talent for verse like Mr. Prelutsky. Just as games that make kids run and jump outside will help them grow strong, poetry can strengthen and grow their understanding of language. After all, poetry is language at play.

If you are a teacher, a parent, or an older sister or brother, the best thing to do is to find writers that shake-up the boring, expected forms of poetry, and read them to a child in your life. If you aren’t sure where to start, here is a brief round-up of some exciting books of poetry for children, with a sample from each.

The Language of Cat by Rachel Rooney

Rachel Rooney is a special needs educator with a growing collection of phenomenal children’s poetry books to her name. She writes to help young people poke at, question, and unravel the possibilities of language to find fun in their own writing, just as she does. Poetry collections by Rooney include The Language of Cat, A Patch of Black and My Life as a Goldfish.

The Language of Cat is a 2012 Carnegie Medal nominee. It delights in wordplay and leaves lyrical riddles for the reader. These delicious poems combine mind-twisting phrases with lush visuals, and will fire the imagination of any poet, young or old.

Who?

Who cast the P from a spell

sold it for profit as sell,

then kept what was left

in a locked letter chest?

And who sucked the O from a hoop,

hopped off with that loop

which she balanced for fun

on the tip of her tongue?

Who stole the E from a cheat

in the street when they met for a chat,

slipped her hand in a bag

and made off with the swag?

Then who plucked the T from a thorn,

carved an ivory pen out of horn

and dipped it in ink…

Well, who do you think did that?

Who Look at Me by June Jordan

June Jordan was an influential writer and activist. Her works covered a broad swath, ranging from essays, to plays, to poetry and children’s literature. She explores themes of race, class, gender, identity, and privilege, drawing on experiences growing up as a child of Jamaican immigrants in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. Jordan was passionate about normalizing African-American English in writing, in order to preserve the community and culture. She went on to write several novels for children, before becoming better known as a political essayist.

Jordan’s first published work was Who Look at Me, is a series of reactions and reflections on paintings of historical African-American subjects. Her poems are alive and bluntly immediate, carrying a spoken feel. They find a beauty in defiance.

Who look at me?

Who see the children

on their street the torn down door the wall

complete an early losing

games of ball

the search to find

a fatherhood a mothering of mind

a multimillion multicolored mirror

of an honest humankind?

*

look close

and see me black man mouth

for breathing (North and South)

A MAN

I am black alive and looking back at you.

Bananas in my Ears by Michael Rosen

Michael Rosen is a prolific writer of children’s fiction and poetry, who has also written for the BBC in radio-plays and newspaper columns. All of his works are inspired by his own life between the ages of six and twelve.

Bananas in My Ears compiles four of his earlier books, each following a rhythm of poems and stories about a fantastically absurd version of everyday life from a child’s perspective. It includes poems about a messy breakfast, exploring the beach, visiting the doctor, and (not) going to bed. It is humorous and dream-like in turns, and will provide a zany read-aloud for young children. Rosen’s work is paired with illustrations by Quentin Blake, a British Children’s Laureate who provided the instantly-recognizable look of Roald Dahl’s stories.

Fooling Around

“Do you know what?”

said jumping John.

“I had a bellyache,

and now it’s gone.”

“Do You know what?”

said Kicking Kirsty.

“All this Jumping

Has made me thirsty.”

“Do you know what?”

said Mad Mickey.

“I sat on glue,

And I feel all sticky.”

“Do you know what?”

said Fat Fred.

“You can’t see me.

I’m under the bed.”

Talking Turkeys by Benjamin Zephaniah

The multi-talented poet Benjamin Zephaniah writes with dub music in mind. His work is meant to be spoken, and uses unpretentious, everyday language to construct his ‘riddims.’ He often writes in a Caribbean accented English to express his pride in being Jamaican-British.

Talking Turkeys is his only collection of poetry written for children, and the first printing of it was sold out in six weeks. His poems can be eclectically short or long, rapid-fire, even nonsensical. His style is laced with humor, yet does not shy away from representing serious issues that Zephaniah advocates for, such as anti-racism, anti-imperialism, animal rights and veganism. Always, his verse is rooted in positive vibes and an upbeat rhythm.

Who’s Who

I used to think nurses

Were women,

I used to think police

Were men,

I used to think poets

Were boring,

Until I became one of them.

Fair Play

Mirror mirror on the wall

Could you please return our ball

Our football went through your crack

You have two now

Give one back.

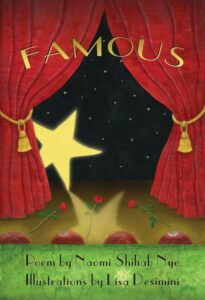

Famous by Naomi Shihab Nye

Naomi Shihab Nye has a broad-ranging body of work in songs, novels, and poetry. She is native to San Antonio, Texas, and has lived in Palestine, home of her father’s family, and these cross-cultural experiences are a major inspiration to her. She has written many books specifically for children, most recently A Maze Me: Poems for Girls. In all of her poetry, the simple language and honesty makes them approachable for young readers, yet meaningful to people of all ages.

Famous was originally a part of her adult poetry collection Hugging the Jukebox, but it was transformed into a picture book, with illustrations from Lisa Desimini. It uses unexpected relationships to redefine exactly what it means to be “famous.” The lush, lively pictures perfectly complement and tease out the playful imagery of this poem.

Famous

The river is famous to the fish.

The loud voice is famous to silence,

which knew it would inherit the earth

before anybody said so.

The cat sleeping on the fence is famous to the birds

watching him from the birdhouse.

The tear is famous, briefly, to the cheek.

The idea you carry close to your bosom

is famous to your bosom.

The boot is famous to the earth,

more famous than the dress shoe,

which is famous only to floors.

The bent photograph is famous to the one who carries it

and not at all famous to the one who is pictured.

I want to be famous to shuffling men

who smile while crossing streets,

sticky children in grocery lines,

famous as the one who smiled back.

I want to be famous in the way a pulley is famous,

or a buttonhole, not because it did anything spectacular,

but because it never forgot what it could do.

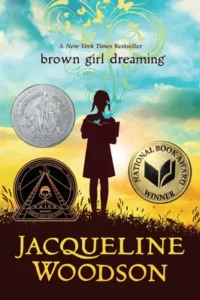

Brown Girl Dreaming by Jacqueline Woodson

Recently honored as theNational Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, Jacqueline knows how to authentically explore the world from the perspective of youth, and does not shy away from hard topics. She writes stories and poems to help children and adolescents find the answers to questions about themselves, and come away with hope.

The Newbury Honor winning book Brown Girl Dreaming is a memoir about her childhood split between Brooklyn and South Carolina in the 1960’s and 70’s. In verse, she tells of the divide between the North and South, her father and mother, of growing up in a time of revolution, and discovering direction in the joy of writing.

A Girl Named Jack

Good enough name for me, my father said

the day I was born.

Don’t see why

she can’t have it, too.

But the women said no.

My mother first.

Then each aunt, pulling my pink blanket back

patting the crop of thick curls

tugging at my new toes

touching my cheeks.

We won’t have a girl named Jack, my mother said.

And my father’s sitters whispered,

A boy named Jack was bad enough.

But only so my mother could hear.

Name a girl Jack, my father said,

and she can’t help but

grow up strong.

Raise her right, my father said,

and she’ll make that name her own.

Name a girl Jack

and people will look at her twice, my father said.

For no good reason but to ask

if her parents were crazy, my mother said.

And back and forth it went until I was Jackie

and my father left the hospital mad.

My mother said to my aunts,

Hand me that pen, wrote

Jacqueline where it asked for a name.

Jacqueline, just in case

someone thought to drop the ie.

Jacqueline, just in case

I grew up and wanted something a little bit longer

and further away from

Jack.